Has Earth’s human population surpassed the planet’s carrying capacity?

Roughly a third of the carbon we have emitted since industrialisation has been absorbed by our oceans. The resultant ocean acidification threatens life on Earth, but carbon is only one of humanity’s waste products.

Mapping the devastation wrought by lesser-known pollutants reveals the elephant in the room of climate change discourse, and raises an awkward but urgent question – has Earth’s human population surpassed the planet’s carrying capacity?

Back in 1970, the global population was just over 3.5 billion. By then it was already clear that our waste products were damaging our environment, and on April 22 of that year, disparate environmental campaigns coalesced to demand action from the US government on the inaugural Earth Day. By the end of 1970, the US Environmental Protection Agency had been formed, and the Clean Air, Clean Water and Endangered Species Acts were passed.

Half a century later, we have failed to realise the promise of the early success of the environmental movement. In the intervening fifty years, the global population has doubled, while climate change deniers have sowed doubt, undermining the science even as the evidence has accumulated, stymying our ability to act. Meanwhile, the remarkable capacity of our oceans to absorb carbon from the atmosphere has swept the problem under the carpet, but at tremendous cost.

The result has been the acidification of the oceans, which threatens all life on Earth. Phytoplankton generates the vast majority of our planet’s oxygen, and ocean acidification disrupts their ability to function. We have managed to induce toxicity in our oceans that is heading towards the levels that induced previous mass extinctions.

Convincing the public that carbon is something to worry about has been difficult. Yet carbon is just one of five major waste products that we are introducing into the environment. By combining geospatial and environmental data, we can begin to grasp the impacts of four other waste products on our geography:

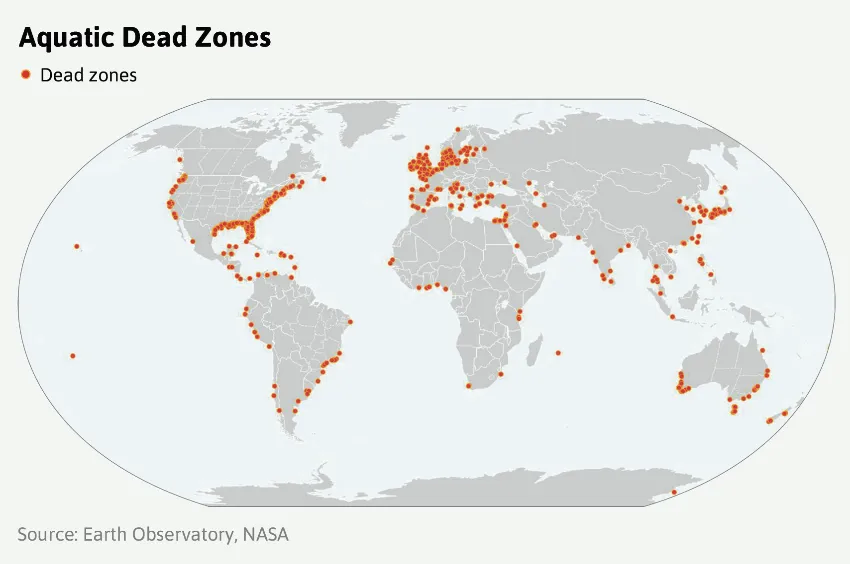

Agricultural and urban runoff is creating ocean dead zones that are increasing in number and expanding in size.

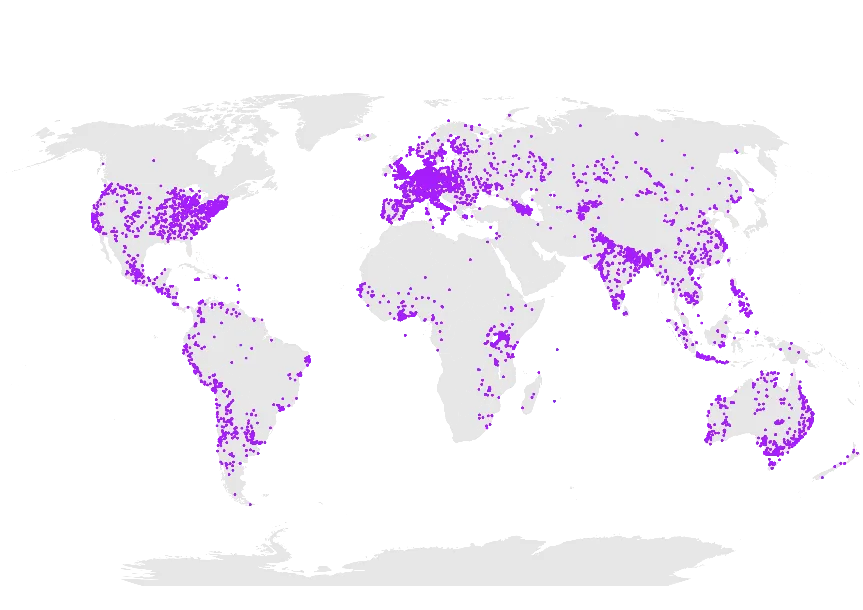

Industrial production and application of endocrine disruptors, heavy metals and radioactive waste are accumulating in our soil and water, creating persistent toxicity. In the image above, the purple dots represent toxic sites.

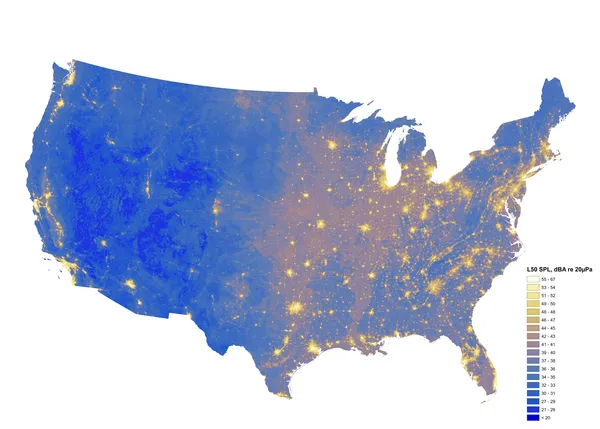

Anthropophony – the noise generated by human activity – has managed to disrupt the basic signalling mechanisms that many animals use for mating, hunting, and navigation. Noise pollution, shown in lighter colours in the map above, corresponds to population centres.

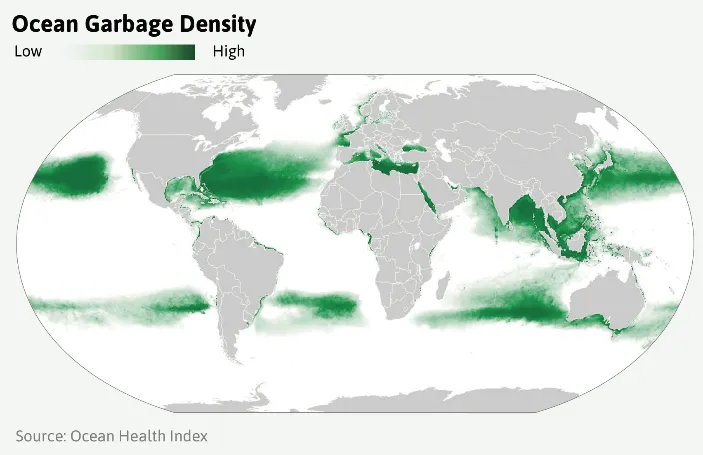

Five continent-sized garbage gyres have accumulated in our oceans, which are damaging marine life and making their way into food chains, including our own.

Geospatial techniques allow us to trace these pollutants back to human population centres or human industry. Underlying these five waste products are five processes that play a part in generating them:

Material extraction

Humanity has extracted materials from the planet to combust for energy and light for thousands of years, but the destruction of forests, mining for coal and drilling for oil has expanded exponentially in the last century.

Industrial agriculture

We have engaged in increasingly industrialised agriculture that has led to continuous tooling of huge stretches of the Earth’s surface, destroying historic wildernesses while also driving waste byproducts into our environment.

Manufacturing

Consumer culture has driven a massive expansion of the manufacturing of products. This process uses vast amounts of natural resources and generates industrial byproducts and mountains of post-consumer waste.

Development

We have expanded the reach of our infrastructure, leaving no terrain inaccessible to development, disrupting ecosystems across the planet in the process.

Urbanisation

As human habitats have become increasingly urban, suburban and exurban, we have paved over our planet with impermeable surfaces that have changed how rivers flow, where plants can grow and disrupted the movement of animals.

It is time to acknowledge runaway population expansion as the fundamental cause of the changes we are seeing in our physical geography. While conversations about population have become a quasi-taboo subject for understandable reasons, our reluctance to discuss it is a foible we can no longer afford. It is now critical that we get down to first principles and ask ourselves, "How many people can the Earth support?" (PDF) For argument’s sake, I have posited the figure of three billion. But we cannot begin to answer this question without using the geospatial tools at our disposal to map the impact our waste products are having on the planet.

Chair, American Geographical Society

Christopher Tucker is Chair of the American Geographical Society, founder of MapStory, a crowdsourced map of geographical change, and author of A Planet of 3 Billion.